During my years of developing software, I wrote a lot of methods. One of the things I love about software development is that it’s basically one big puzzle. When you have the pieces you can make everything fit. But the pieces are not all unique. Which piece is better depends on several factors; versions, legacy code, architecture, and performance. And the last one is really important. But how do you know which approach is better for performance and memory usage? By benchmarking C# code. And BenchmarkDotNet is a great tool to do that.

There are different approaches possible to do what you want to do. I know, from my head, 3 ways to format a date. All 3 have the same outcome, but different approaches.

Table Of Contents

NEW and FREE!

Introducing: Kens Learning Paths

A new way of practicing what you just learned. With exercises that are specified for a specific subject, you can now try it yourself and figure out if you understood the content of a lesson.

Learn, practice, implement.

The Idea Behind Benchmarking C# Code

Benchmarking is a way to evaluate something by comparison with a standard. Assume you have two methods with the same outcome but have different codes to get to that outcome. Both work, with no problems, but you want to know which is better in the sense of performance. You can run them both and compare the speed and memory. With that information, you can decide which approach is best.

You could also use benchmarking to check if your code is lacking at some point. There are tricks to increase the performance of your code. With benchmarking you can check if you have gained or lost performance. Note that benchmarking is not like an SQL profiler. Yes, you can profile your code, but not the database.

What it does, in theory, is run your code and do some testing. It depends on which tool you use because there are multiple tools and they all work slightly differently.

BenchmarkDotNet

One of the tools you can use is BenchmarkDotNet. This is an open-source library that has a very pleasant way of working. You basically write unit tests for the pieces of code you want to benchmark. This makes it feel really familiar to use because we all make unit tests (…Right?).

As I will show you in the next chapters, benchmarkDotNet is easy to use. It takes away a lot of work. I have been using another library that took a lot of configuration. BenchmarkDotnet does not.

Although you can use BenchmarkDotNet for a lot of code, I would keep it to methods or small pieces of code. I wouldn’t start using it for testing APIs or other front-end applications. There are other tools for that. Also, don’t use it to unit test the code.

Instead, use BenchmarkDotNet for small pieces of code. Don’t test whole systems (that too has other, dedicated tools). In most cases, you want to benchmark algorithms or a few lines of code. We call these micro-benchmarks.

Benchmarking C# Code

Alright, let’s start benchmarking with benchmarkDotNet. There are two approaches; via a BenchmarkDotNet template or from scratch. The first one will create a new project with everything you need to benchmark your code. The second is… Not the first; you will need to create your project and files. Or just files if you want to store your benchmarking in an existing project.

I will be using the template version. Just because it’s easier and it gives me everything I need.

Install And Use The Template

Installing the BenchmarkDotNet template is really easy. Open a command prompt or use the Visual Studio command and execute the following command:

dotnet new install BenchmarkDotNet.Templates

Then you can start Visual Studio and create a new project. Look for the template with the name ‘Benchmark Project (.NET Foundation and contributors).

Then we need to set up the project. First, we give it a name. I call mine BenchmarkDotNetDemo.Suite and the solution BenchmarkDotNetDemo.

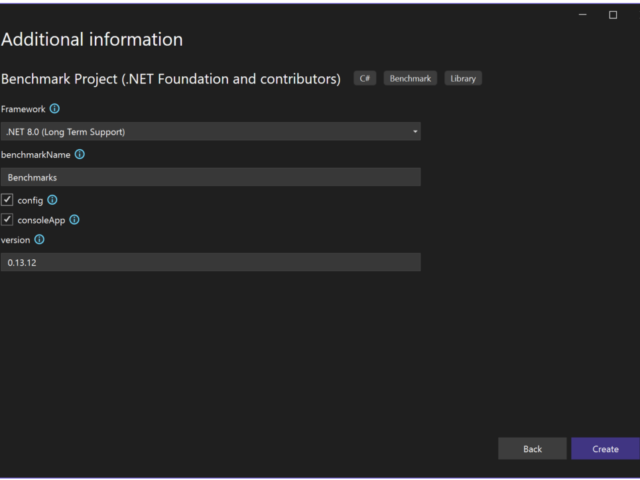

The additional information is a bit different. Of course, we need to choose .NET version – I use .NET 8. But we also need to name our benchmarks. I keep this one default. I also check config, which gives me a configfile. Not going to work with it much, but so you know it exists. I leave the consoleApp checked because I want to run it. This option will create a console application that allows you to run the benchmarks.

Keep the version as it is. This will be the newest version available.

The Project For Benchmarking C# Code

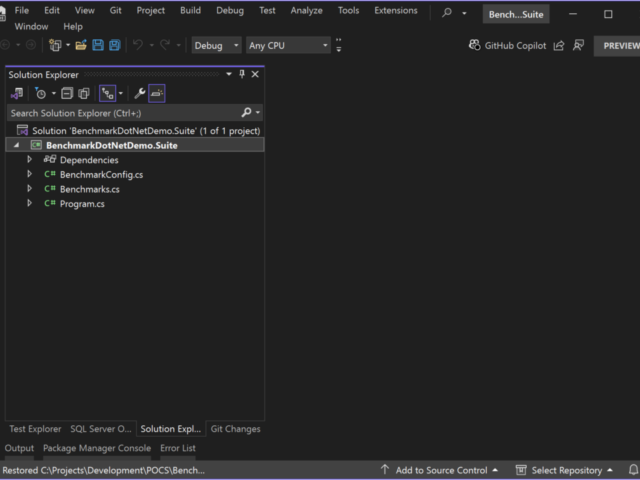

Now we have a new console application. The new project gives us 3 files:

- benchmarkConfig.cs

Here you can configure how BenchmarkDotNet runs the benchmarks. - Benchmarks.cs

Here you create the actual benchmarks. I will come back to this later. - Program.cs

I guess you already know what this one is. But when you look at the code it is just code to run the benchmarks.

The idea of this structure is pretty simple: You run the console application which will run the benchmarks with a configuration. You don’t have to do anything else for this. Benchmarking with C# is pretty easy because you only need to create the code to benchmark.

Creating A Simple Benchmark Test

There are different ways to concatenate a string; these are a perfect example for benchmarking with C#. You can use a StringBuilder to build a string, but you could also use a List<T>.

The Benchmarks

I changed the class Benchmarks to the following:

[Config(typeof(BenchmarkConfig))]

public class Benchmarks

{

[Benchmark]

public void Scenario1()

{

List<string> lst = new();

for (int i = 0; i < 100; i++)

{

lst.Add(i.ToString());

}

string finalResult = lst.ToString();

}

[Benchmark]

public void Scenario2()

{

StringBuilder sb = new StringBuilder();

for (int i = 0; i < 100; i++)

{

sb.Append(i.ToString());

}

string finalResult = sb.ToString();

}

}

Both scenarios do the same; they have a for-loop that runs 100 times and adds a number to a List<string> or a StringBuilder. They are the same except for the List<string> and the StringBuilder. Let’s run BenchmarkDotNet to see if they are different in performance.

Running BenchmarkDotNet

Let’s start the console application and see what happens. Well, a lot… I could take a while before it’s done.

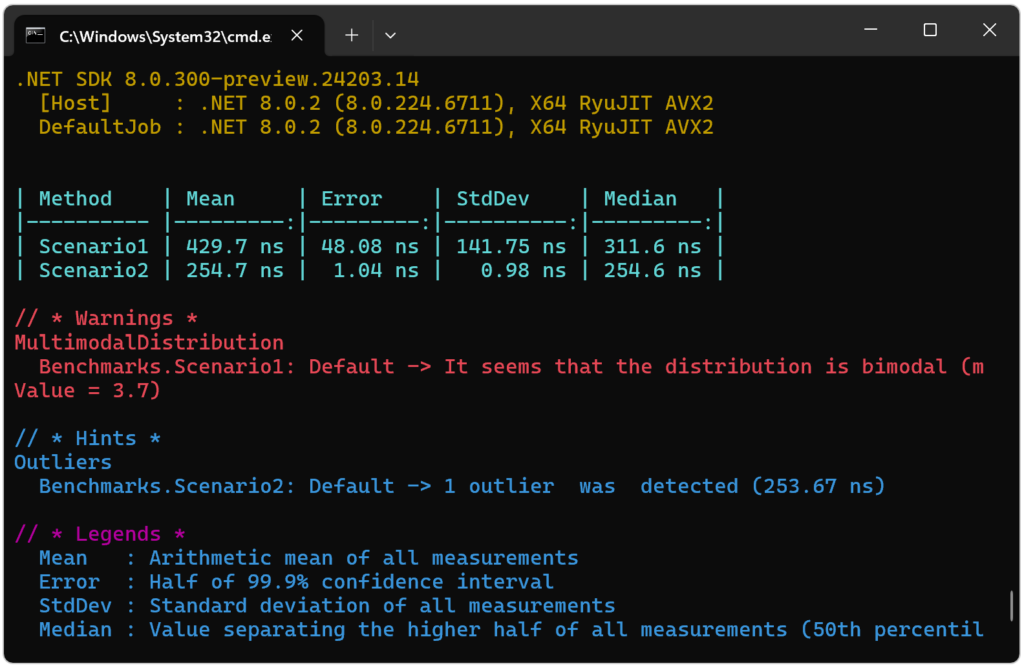

After a while, you will see a result like this:

Ooh, look at all the pretty colors!

I will talk about the result a bit later. I want to address something first: The warning Benchmark was executed with attached debugger.

Run It In Release

But the summary does say something about the attached debugger. For a better result, it’s better to run the application in release mode. Even better is to close all other applications, open a command prompt, and run the following command inside the solution folder:

dotnet run -p BenchmarkDotNetDemo.Suite.csproj -c Release

The same process starts and if could take another while before it is done.

The result is slightly different but the first warning is gone. But we still have another warning.

Bimodal Benchmarking C# Code

A bimodal distribution means that there are two peaks. This is caused when the same entities peak in different stages. For example, in a car race; 10 cars start simultaneously, but 5 finish first and the other 5 finish later. This generates two peaks.

It could be useful to investigate why this is happening with our benchmark, but I would leave it as is for now.

Reading The Results

Let’s take the last results and what they mean.

| Method | Mean | Error | StdDev | Median |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario1 | 429.7 ns | 48.08 ns | 141.75 ns | 311.6 ns |

| Scenario2 | 254.7 ns | 1.04 ns | 0.98 ns | 254.6 ns |

Each benchmark has its own row. It’s important to give them a good name. Use names that tell what the benchmark is benchmarking.

- Mean is the average performance of your code based on the measurements taken during benchmarking.

- Error is the margin of error associated with the mean value calculated from the benchmark measurements.

- StdDev provides additional information about the spread or dispersion of the measurements. It allows you to understand the consistency or variability of the code’s performance

- Median represents the middle value in a sorted list of measurements

If you take the result and the meaning of the columns we can say that Scenario2 (the StringBuilder) has a better result because it has a lower mean, error, and standard deviation values. It is also faster and more consistent performance.

Besides the console table, you get more ways of reading the result. When the benchmarking C# code is finished, a new folder is created; BenchmarkDotNet.Artifacts. This folder contains a log and files with the results. By default, you get a CSV, HTML, and a log file. They all give the same information as the information you see in the console app.

Note: These files are created only when you run it with the command prompt.

Conclusion On Benchmarking C# Code

With a fairly simple setup, you can use BenchmarkDotNet to benchmarking C# code. You just install the template, create a new project, enter the code you wish to benchmark, and off you go.

I do agree that reading the result is a bit tricky, but once you understand what the different columns and definitions mean, it’s pretty awesome.

Benchmarking C# code has helped me create better code. Not only for the performance but somehow also for the way I write code. It helped me discover problems and make everything faster.

Just note that a single benchmark does not represent a real-life application. I benchmark the API for Kens Learning Paths a lot, but it does not cover the fact many people using it. Benchmarking C# code only gives a local estimate of the performance of your code.