Lately, I have seen a lot of articles about clean code. And that’s good! When I was teaching people asked me as well what my vision of clean code is. I never understood why people ask about ‘my vision’. I just read about Robert C. Martin, a.k.a. Uncle Bob, and apply clean code with C#.

But some people read a book and follow it as the bible of clean code. I believe there is more to it than just someone telling his best idea of clean code.

My Vision On Apply Clean Code With C#

My vision of clean code is based on experience and learning from others. I have a few ground ‘rules’ I stick to and try to teach that to others who are interested. These are not the only way to go and you may not agree with some, but the following tips are some I have been using for many years.

I will focus mostly on clean code with C#, since that is what language I generally use. But you can apply clean code in most languages.

The Team

Clean code is not some given book, like the 10 commandments. You will discover and develop it when you work your way up to being a good developer. Yes, there are good developers with terrible code who usually don’t work in a team. Because as a team you set certain ground rules on how team members should be making code. The idea of this is simple: Everyone in the team develops code in the same way, so everyone can read it, change it, and continue on it.

We call these ‘rules’ code styles. It’s most of the time a (digital) document that describes what kind of decisions the team has made on certain developing styles.

It can be about anything. Like using var or not, using brackets with a single-lined if statement or not, and declaring variables with capitals, underscores… Or not. But also things like the maximum number of parameters a method should receive.

This way the team members know how to develop certain codes. Sadly, I have seen this kind of coding style in 3 companies I worked for… Out of the 21. It usually caused frustration, (unresolved) discussions, and even a fight.

So, how to create this document of coding styles? Well, it starts with the team getting together and talking about the current code. Maybe some members have questions or disagreements about certain choices of other members. It’s not a race about who is right and who is wrong, but it’s about getting the team together in a way so everyone can read and understand the code. If two members of the team can’t agree, it’s usually the lead developer that makes the final decision.

Some Rules I use

Besides the team, it’s also important for you to make decisions on how to create clean code. If you are working on a project by yourself you could go with the flow and do whatever seems fit. But, what happens if someone comes and helps you? Or if you publish your code online, like in a question or tutorial?

So, to help you decide your way and the idea of clean code, here are the tips that I use.

To Var Or Not To Var

I think most of us developers know this discussion: Should we use var or explicit declaration? I’ve been using both because my employers asked me to. But when I work on a project by myself, I use var. Yes, past tense.

Using var looks like this:

var someString = "Hello world"; var client = new HttpClient();

Var is an alias of what’s on the right side of the =. So in the first line, var is a string. In the second line, var is an HTTPClient. A big advantage is that you don’t have to type the type twice. So… Var is for lazy people? Nah, it’s just easier. It’s not about being lazy or not. It’s a way of declaring a variable.

But it does make the code a little bit harder to read. If you use explicit declaration on the previous code it would look like this:

string someString = "Hello world"; HttpClient client = new HttpClient();

In the example above, you can see the types of variables quickly. This way of declaring a variable is enforced in example code in tutorials or teaching. Another advantage is that you can now remove the type on the right side and just type ‘new’. For example:

string someString = "Hello world"; HttpClient client = new();

This doesn’t work on the string since it doesn’t have an initializer.

I used var a lot, but I am using explicit way more. Why? The new way of initializing a type has become more efficient (read: less code) and it’s easier to read. In some cases I still use var, but that’s limited to unit tests.

Someone told me that using var was insufficient. Because the application has to convert the var to the actual type. This is not true; at compile time the var is being replaced by the actual type, making the var not insufficient when running the application.

Brackets

The use of brackets is well-known in C# and in other languages. It defines a block of code, like a method, class, if-statement, and so on. In some cases, you can remove the brackets.

We all know this piece of code:

if(val == "somestring")

{

Console.WriteLine("Correct!");

}

A simple if-statement with one line within the block. But you can remove the brackets since there is just one line. The advantage is that you reduce the number of brackets, making the code look a bit cleaner and you can focus more on the code.

if(val == "somestring")

Console.WriteLine("Correct!");

Maybe the example code does not really show the obvious reason for removing the brackets, so here is a bigger example with brackets:

string greeting = "Hello world";

if(greeting.GetType() == typeof(String))

{

// Yes this is a string

Console.WriteLine(greeting);

}

else

{

Console.WriteLine("This is not a string.");

}

if(greeting.Length > 5)

{

Console.WriteLine("The length of the greeting exceeds 5 characters.");

}

else

{

Console.WriteLine(greeting);

}

It’s a simple piece of code of 20 lines. We can reduce the number of lines to 11 by simply removing the brackets:

string greeting = "Hello world";

if(greeting.GetType() == typeof(String))

Console.WriteLine(greeting);

else

Console.WriteLine("This is not a string.");

if(greeting.Length > 5)

Console.WriteLine("The length of the greeting exceeds 5 characters.");

else

Console.WriteLine(greeting);

The downside of this is when you add another line to the body of the if-statement. Brackets can be removed when you have just one line. If you add more you’ll need to add the brackets again.

string greeting = "Hello world";

if(greeting.GetType() == typeof(String))

Console.WriteLine(greeting);

else

Console.WriteLine("This is not a string.");

Console.WriteLine("Please use a string"); // This line will always be printed.

if(greeting.Length > 5)

Console.WriteLine("The length of the greeting exceeds 5 characters.");

else

Console.WriteLine(greeting);

Line 7 has been added. As you can see the line jumps to the left, showing you it’s not a part of the else-statement. Line 7 will always be executed, even when the greeting is a string.

I am not a fan of brackets as they kinda blur the code. I try to reduce the number of brackets to a minimum if possible. This usually also helps to notice other refactor options, like in the code above. We can reduce the number of lines even more.

string greeting = "Hello world";

if (greeting.GetType() == typeof(string) && greeting.Length <= 5)

Console.WriteLine(greeting);

else if (greeting.Length > 5)

Console.WriteLine("The length of the greeting exceeds 5 characters.");

else

Console.WriteLine("This is not a string.");

When I apply clean code with C#, this is one of the things I look at.

Comments

I already posted a whole blog about comments and how (not) to use them. So here is a small summary.

Don’t use comments

…

Thank you.

Comments can blur the code, making it harder to read the code. The only times one should use comments are:

- When you work on a project alone.

- To write summaries in an interface.

- Explain a really hard calculation

Don’t use comments to:

- Explain the method.

Maybe the name of your method is not correct. - To mark you need to do something later.

Use a scrum board for this. - Tell your team members to leave the code alone.

Camel case and Pascal case

- The way we declare variables, methods, and classes is important. Not only the name but also how we write them. It’s a convention so we can see what a specific name is. Camel and Pascal casing are a big part of this. They define how to use capital letters in a name:

- PascalCasing

- camelCasing

Here I follow the Microsoft code conventions, meaning I follow their view on when to use Pascal casing or when to use camel casing. There is a whole document you can follow on this topic. But it’s pretty simple:

- Public types are PascalCasing

This includes, but is not limited to, classes, interfaces, methods, properties, and enums. - Private types are camelCasing

This includes but is not limited to, methods, variables, and private properties.

An example:

namespace ExampleCasing // namespace = PascalCasing

{

// interface = PascalCasing. Mind the capital I and E.

public interface IExampleClass

{

string Name { get; set; }

}

public class ExampleClass // class = PascalCasing

{

public string Name { get; set; } // public property = PascalCasing

private DateTime currentDateTime; // private class variable = camelCasing

public ExampleClass() // class = PascalCasing

{

string exampleVariable = "Hello world"; // private variable = camelCasing

}

private void DoSomething() // private method = camelCasing

{

...

}

}

public enum Gender // enum = PascalCasing

{

Male,

Female,

Other

}

}

Naming Conventions

To apply clean code with C# is much more than how you code. It’s also how you name variables, classes, and so on. Camel casing and Pascal casing are both parts of the naming convention. But there is more to naming convention than just these two.

There are a few rules I stick to:

- A name should be short.

private void ExecuteSQLStatementOnSQLDatabaseThatIsLocatedInAzureWithAConnectionStringInAppSettings() - A name should be explainable.

private void Execute() … Execute what?

private void ExecuteSQLStatement()… Ah, that! - Only use letters.

Don’t use numbers, underscores, or other characters. Some are not even allowed.

private void Execute_Sql_Statement().Exception on the unit test methods. - Don’t use prefixes on variables

string sGreeting = “Hello world”;

var lAmount = 1029265527892;

Keep the words readable

A variable, class, or method name that consists of multiple words should have capitals on each word. For example:

private string helloWorld { get; set; } // Correct; capital W

private string executestatement() // Incorrect. The 's' of statement should be a capital S.

{

...

}

public class SomeNewClass // Correct

{

}

The reason why we do this is to make the names more readable. On line 2 for example. It’s harder to read since you need to look for the words. Lines 1 and 7 are easier.

Underscores

Microsoft coding conventions dictate that when you have private property on a class you should add an underscore as a prefix. This is one of the Microsoft ‘rules’ I don’t use. A variable written with camel casing shows that it is private.

public class ExampleClass

{

private DateTime currentDateTime;

private string _greetingText;

}

Method length

Some people say a method should be no longer than 5 rows of code. If that includes the brackets, I don’t know. What I do know is that it’s almost impossible to accomplish this. Yes, you can create hundreds of small methods, but does that help create clean code?

What I try to do is keep my methods between 10 and 20 lines of code, keeping the single responsibility principle in mind: A method or class should have one responsibility. Sometimes I go over those 20 lines of code, but usually with a reason. Don’t stress about it too much.

Tip: Just start writing code in one method. When everything works like it should, with unit tests, try to break up the method into smaller methods. In the end, you will end up with small methods with around 10 to 20 lines. This is a great way to apply clean code with C#.

Parameters length

A method can have parameters. I like to keep them to a minimum of 5, If a method gets more, I usually create an object that holds those parameters and uses that single object as a parameter variable.

Some people think 3 is the max, which is doable. Keep the single responsibility principle in mind. If you put properties together in one single object, that have nothing in common, you’ll break that principle.

Line length

Common practice dictates that lines of code should not exceed the screen. I am really struggling with that one.

What it means is that you don’t scroll in the editor and you keep all your code in view. This is almost impossible due to the different resolutions of screens. The resolution of my laptop is 1920×1080. But if someone has a lower resolution, let’s say 800×600, the code that looks fine on my screen might create a scrollbar on the lower resolution.

Another problem is Visual Studio or different editors in general. Take a look at the screenshot below, which is my Visual Studio.

Everything I need: Editor and Solution Explorer. Other windows, like the SQL browser, GIT, and Error List are not needed all the time, so I minimize or hide them.

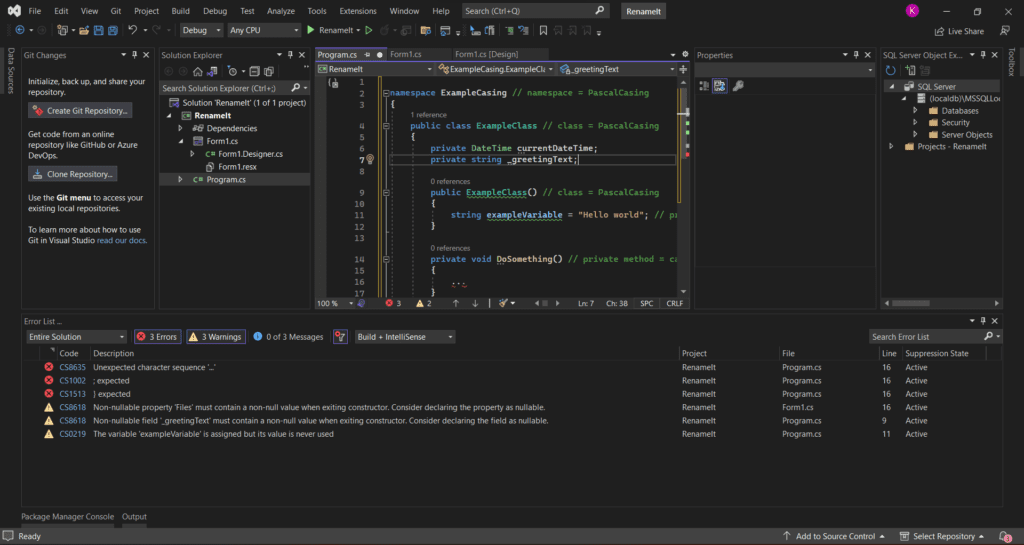

No, take a look at the screen of someone who likes to keep track of everything:

Who decides the length of the lines? How many characters are allowed per line? My advice: Keep your editor clean.

Conclusion On Apply Clean Code With C#

These are basically the rules of clean code and coding conventions I try to follow. Again, these are things I learned during my work and what I have found. You don’t have to agree. If you have any ideas or add-ons, please let me know in the comments.

To apply clean code with C#, or any language, is a good way to keep your code maintainable and readable. Just don’t go berserk with it. Do what you can and don’t spend hours and hours to perfect your code. Perfect code doesn’t exist.